Recently, while processing the Rogers Family Papers, I came across a curious set of scrapbook pages related to a certain “Black Hand Society.” The pages, dating to 1907, were signed by and referenced a number of the grandchildren of Henry Huttleston Rogers, the Standard Oil magnate whose philanthropy in the Town of Fairhaven is well known.

The scrapbook begins innocently enough, with a petition apparently signed by eight of Rogers’s grandchildren and the same number of their friends requesting “that the stones on the beach near the float, and at the end of the pier, be removed, as there is a danger of hitting them in diving.” While the petition would certainly not hold up in a court of law, having been flawlessly “signed” by children including Henry Huttleston Rogers III, then just two years old, and his cousins, “Billie and Bobbie” (William and Robert) Coe, then six and five, respectively, I took it as a bit of summer fun by group of children who spent their summers swimming, boating, and exploring the grounds of Rogers’s 85-room Fairhaven mansion.

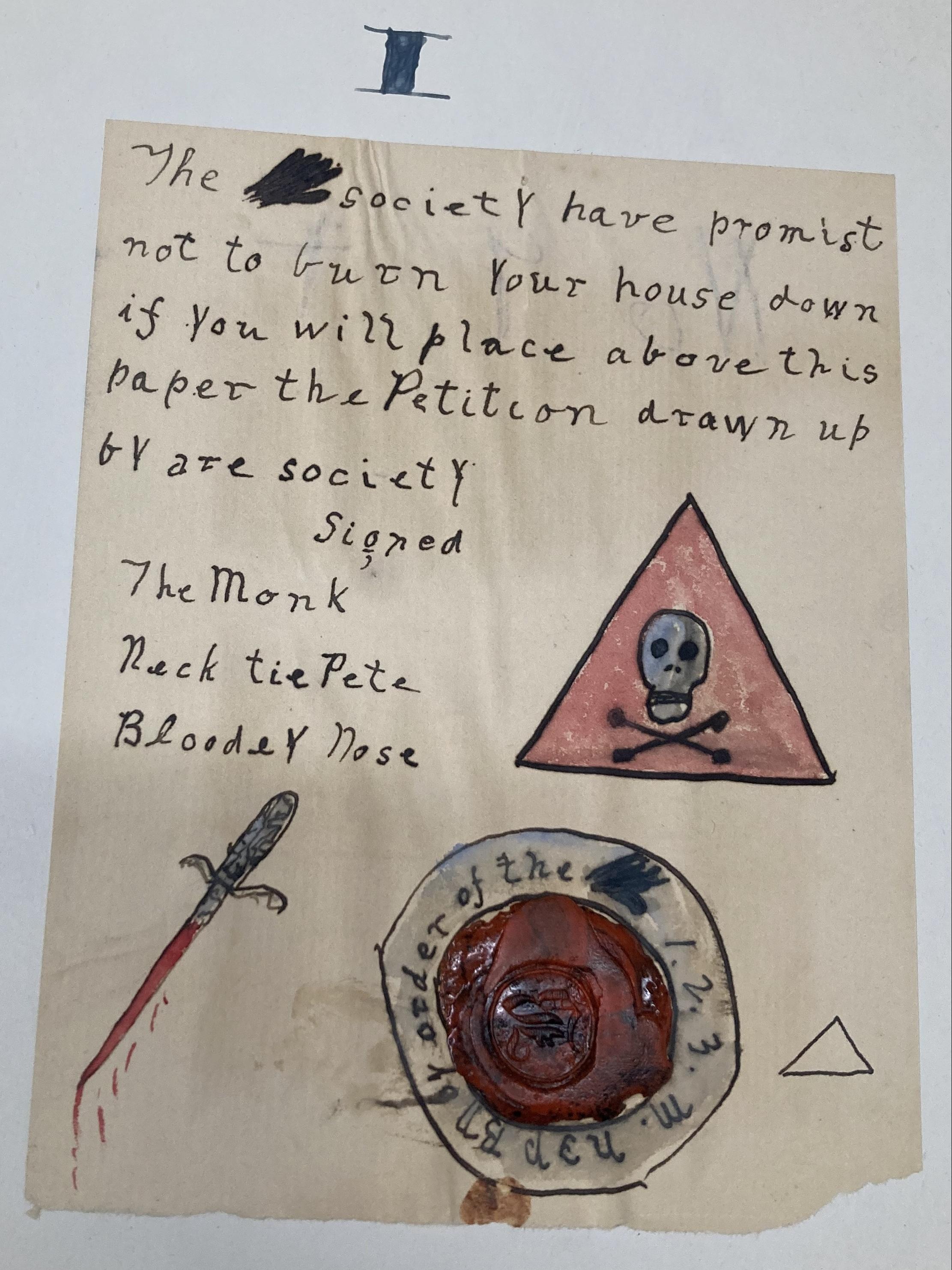

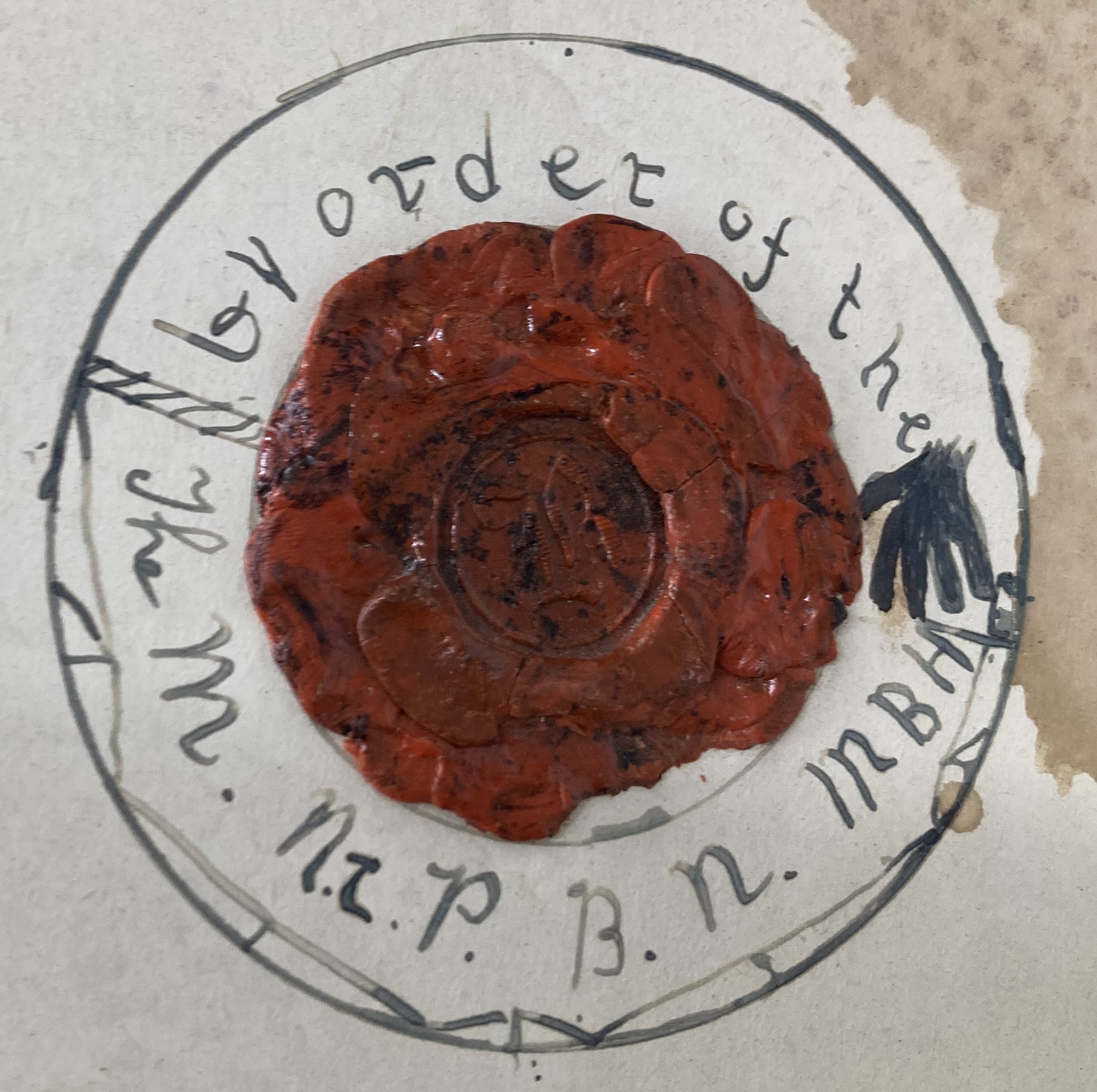

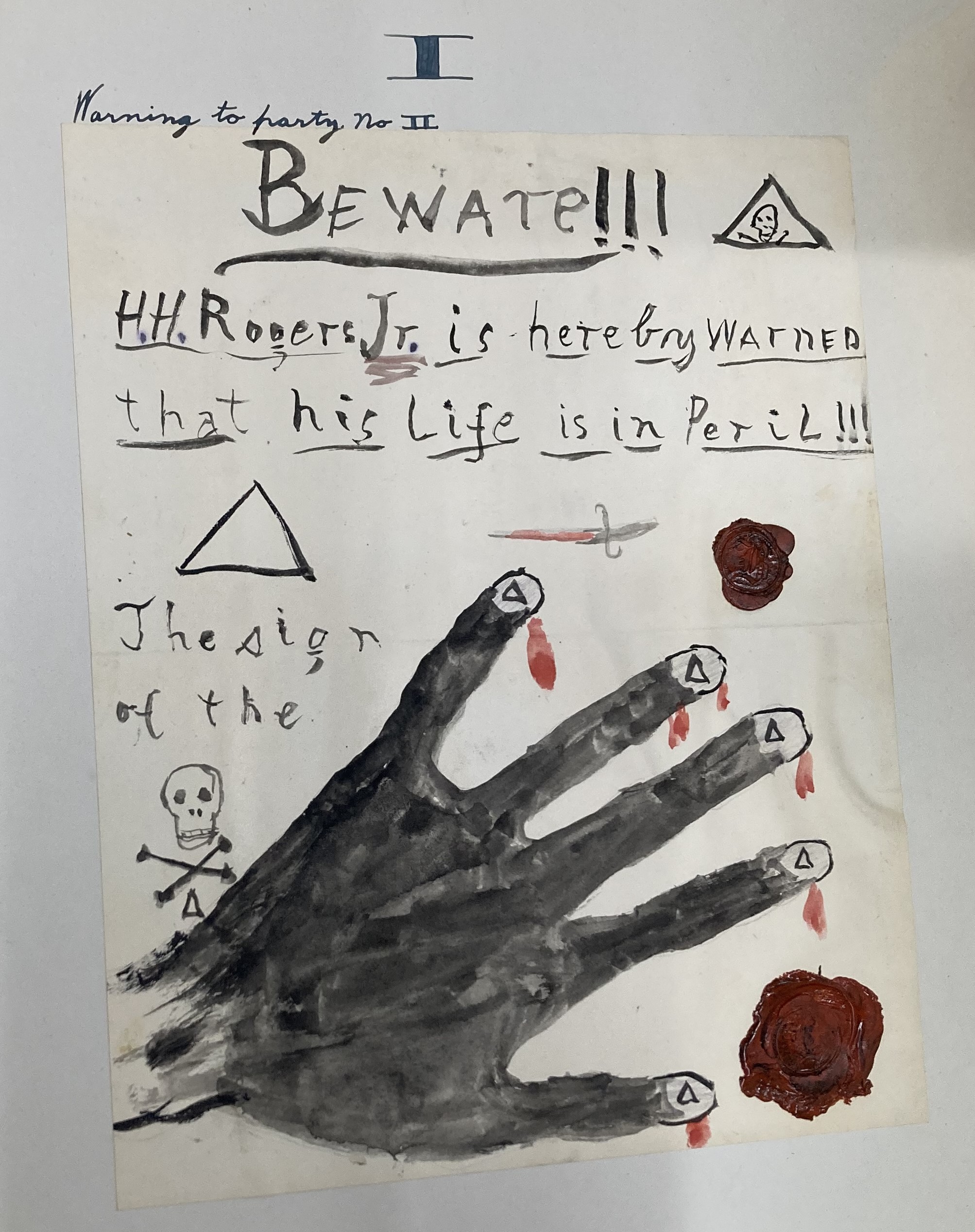

But the reverse of the page is more ominous. It bears a large red wax seal, encircled by initials and the words “by order of the” and a drawing of a black hand.

To me, the drawing immediately called to mind a much more famous Black Hand Society, the Serbian secret society formed in 1901 whose Gavrilo Princip would, in 1914, assassinate Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, igniting the fuse that would lead to World War I. Could the young Rogers children be evoking such a notorious organization?

Another possibility I hadn’t considered emerged as I researched the possibility of the Rogers children knowing about the Serbian militant organization in 1907. Their “Black Hand Society” could, and likely did, refer to any of several extortion rackets run by Sicilian and Italian-American criminals in the United States beginning in the 1890s. These organizations also went by the moniker “Black Hand,” and their tactics included sending threatening notes printed with black hands, daggers, and other menacing symbols to merchants and the wealthy, seeking to extort money on pain of death or destruction of property. So widespread was the Black Hand by the early twentieth century that the organization would threaten a member of the extended Rogers family only a few years after these scrapbook pages were created. In March of 1910, Black Hand members attempted to extort money from the Italian tenor Enrico Caruso, brother-in-law of Henry Huttleston Rogers’s son-in-law William Benjamin.

As I continued to flip through the scrapbook pages, the allusions of the Rogers grandchildren’s “Black Hand Society” to the criminal syndicates of their day became clearer. The pages contained a number of pretend orders, petitions, and notices related to the goings-on in the “City of Rogerster” – a fictitious city invented by the Rogers grandchildren whose name played on that of the nearby real town of Rochester. One notice signed with a black hand dripping blood, a dagger, and a skull and crossbones warned Henry Huttleston Rogers Jr. “that his life is in Peril!!!” Another order promised a $5,000 reward from the Black Hand Society for the “capture and conviction of [Henry] Roger[s] Benjamin, alias ‘the Monk,’ alias ‘Backwoods Rog,’ Henry Broughton, alias ‘Light Foot Jerry,’ alias ‘Money Bags Harry,’ [Urban] Huttleston Broughton, alias ‘Dandy Dick,’ alias ‘Necktie Pete’ and James Warren, alias ‘Jimmy the coffee cooler,’ alias ‘Bloody Nose’.” The four were evidently wanted for “Hightway-Robbery (sic), Murder, Counterfitting (sic), Malicious Destruction of Property, and Trespass.”

Grandfather himself – Henry Huttleston Rogers—was sometimes referenced by the members of the Black Hand Society. One announcement dated September 13, 1907, claimed that “as the result of a conference with Andrew Carnegie, held yesterday by submarine telephone, we wish to announce that there is prospect of an immediate settlement between the Black Hand Society and the authorities of Rogerster. Mr. Carnegie expressed his regret at not being able to preside at the meeting, but has appointed his friend Mr. Rogers, Senior, to act as arbitrator, and declares his entire confidence in Mr. Rogers’ ability to pour oil upon these troubled waters.”

After initially being startled by the Black Hand symbolism, I came to realize that the pages documented something rarely found in archival collections: evidence of the day-to-day lives of children, told from the perspective of those children. Certainly, the imagery found in the scrapbook pages is more violent than modern sensibilities would like to see from children. Certainly, these children were not typical of their day; their grandfather’s unfathomably vast fortune meant that they would always live in comfort, that they would always enjoy better educational opportunities, medical care, and social standing than their peers. (That their scrapbook even survived to be preserved by a twenty-first century archivist is evidence of their enormous privilege.) And yet, to see an entire imaginary world inhabited by early twentieth century children unfold in seven double-sided pages is a remarkable thing. It’s history you can almost reach out and touch – a moment of familiarity.

You never know what you’ll find in the archives! We hope you’ll make an appointment to research with us soon.